Rust For 1 Week

I've always wanted to give Rust a "go" (pun intended as I previously wanted to try out Go and then forgot about it mid-reading the tour). Why not do that now?

Day 1

I've had this interactive book in my open tabs for ages at this point. Time to actually read it.

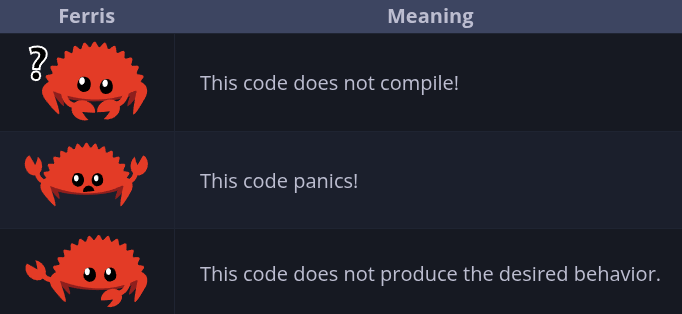

As far as the introduction goes, it seems the Rust book is serious/rigorous, especially when it comes to signaling the different ways a program fails:

Immediately after seeing this table, my educated guess was that the book will be delving deep into the borrow checker and the many intermediary checks that are done by the clever rust compiler pipeline. I'm not an expert in compilers and how written code gets magically transformed into machine code, but recently I saw this video and saw that compared to pretty much any other compiled language, rust adds a bunch of extra steps that are supposed to be modern quality of life improvements. I am excited to see how this book begins.

This book organizes chapters in two categories:

You’ll find two kinds of chapters in this book: concept chapters and project chapters. In concept chapters, you’ll learn about an aspect of Rust. In project chapters, we’ll build small programs together, applying what you’ve learned so far.1

Aperently the image I just pasted here is related to this paragraph:

An important part of the process of learning Rust is learning how to read the error messages the compiler displays: these will guide you toward working code. As such, we’ll provide many examples that don’t compile along with the error message the compiler will show you in each situation. Know that if you enter and run a random example, it may not compile! Make sure you read the surrounding text to see whether the example you’re trying to run is meant to error. Ferris will also help you distinguish code that isn’t meant to work: (image) In most situations, we’ll lead you to the correct version of any code that doesn’t compile.1

Cool. Let's dive in further.

I made sure that I have rustup and the latest rust compiler toolkit.

rustup update

rustc --version

# rustc 1.88.0 (6b00bc388 2025-06-23) (Void Linux)

cargo --version

# cargo 1.88.0For me, I had rustup - the install script - in the Void package repositories, but the method listed by the Rust team in the book was via a secure curl command. Honestly, I would prefer my trusted repositories any day of the week as opposed to downloading an auto-install script.

Also, offline documentation is available via rustup doc which comes in handy as I have unreliable WiFi where I am right now.

I finished chapter 1 pretty easily, it introduced a Hello, World! example, rustc and then cargo with a bunch of the common commands that are used with it. I find it nice that the checking process and fast compilation for debug is the default and how cargo is documented as a whole and how unified it is. It seems much friendlier than other build ecosystems I've tried thus far (but to be honest, pip and the python development ecosystem chaos as a whole being my most used says a lot as well).

Chapter 2 promises to build a random number guessing game.

It introduces the concept of mutability of a variable and how to use it from the very beginning. Here's the most interesting snippet at first sight:

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");I find it interesting how the mut keyword is needed both when creating a new mutable variable and when said variable is passed by reference. I also like how there's an expect statement/method(?) taking care of IO quirks.

Apparently the full correct explanation is this:

The

&indicates that this argument is a reference, which gives you a way to let multiple parts of your code access one piece of data without needing to copy that data into memory multiple times. References are a complex feature, and one of Rust’s major advantages is how safe and easy it is to use references. You don’t need to know a lot of those details to finish this program. For now, all you need to know is that, like variables, references are immutable by default. Hence, you need to write&mut guessrather than&guessto make it mutable. (Chapter 4 will explain references more thoroughly.)1

The key highlight here is that references are "immutable by default". That's one interesting quirk.

Apparently the .expect line is much more clever than I thought at first. But that will be explained in further detail down the line.

As for printing text nothing interesting has happened until seeing this:

println!("You guessed: {guess}");Nice, rust can evaluate expressions inside of strings without any additional syntax like python's f-strings. Instead anything inside curly braces in a string gets evaluated, also empty curly braces in println! at least means that an expression passed as another argument after the string gets shoved into the original string. I apologize if I'm not explaining things very rigorously. I'll let the book speak:

let x = 5;

let y = 10;

println!("x = {x} and y + 2 = {}", y + 2);This code would print x = 5 and y + 2 = 12.

Day 2

I've had this video from No Boilerplate saved and now that I've read some of the rust book I was able to absorb it, let's see how much of an enhancer to this experience it is. Also, great YouTube channel.

The guessing game was a fairly fun learning experience, I took away many things especially the quirks regarding comparing in rust. My final code ended up being:

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

use std::cmp::Ordering;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

//println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

loop {

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

let guess: u32 = match guess.trim().parse() {

Ok(num) => num,

Err(_) => {

println!("Please enter a valid number!");

continue;

}

};

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"),

Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"),

Ordering::Equal => {

println!("You win!");

break;

}

}

}

}I really like how match statements come together with the enum paradigm rust seems to enforce heavily for "outcomes" - this example had Ordering and Result, which give a set of valid variants, matching through those is fun and makes me think more of what can happen in writing my program to make sure edge-cases are covered.

The chapter also featured ranges, and IO string processing, as well as how to use external crates. All introduces easily. Let's see chapter 3, Common Programming Concepts.

The first sub-chapter talks about:

- mutability - variables, declared by

letare by default immutable and changing the value of an immutable variable is forbidden unless themutkeyword is used in the declaration. After a variable is marked as mutable, it can change its value as many times as possible in other parts of the code. - constants - values declared by the

constkeyword. These don't change at any point during a program's execution and are usually "all uppercase with underscores between words". They also need to be a constant expression, "not the result of a value that could only be computed at runtime". - Shadowing - this is very interesting: it basically means that you can reuse the variable name after assigning it to a different expression and even a new data type. they also have this behavior of overshadowing which means that the last declaration in the scope is the one that's going to be used by code in that scope, the book explains this pretty simply:

fn main() {

let x = 5;

let x = x + 1;

{

let x = x * 2;

println!("The value of x in the inner scope is: {x}");

}

println!("The value of x is: {x}");

}This prints a value in the inner scope of 12 and a value at the end, in the outer scope of 6.

I find it interesting how this is seemingly the preferred way of changing / "casting" to another type, as opposed to how other languages do this. I am also a fan of the fact that overshadowing can change the type and/or value of a variable at once, without necessarily making said variable mutable, for other parts of the program to modify. This, I think, is great.

For example:

let spaces = " "; // OK

let spaces = spaces.len(); // OK

spaces = 30; // Not OKSo you could use overshadowing to change the value / value and type of an immutable variable at will and not worry about further parts changing the new value, well, at least if we're not having a conflict of scope, but if you're doing this you probably want the inner scope value to be different from the outside for a reason anyways, otherwise you'd use a const I imagine.

The book spends the last paragraphs of this sub-chapter detailing how using the mut keyword wouldn't be able to change the variable type.

let mut spaces = " "; // OK

spaces = spaces.len(); // Not OKNice, but the main point should be how overshadowing can be used to change values and data types more predictably.

Also this means that, overshadowing, in conjunction with mut can make this work:

fn main() {

let spaces = " ";

let mut spaces = spaces.len();

spaces = 30;

println!("The length of spaces is: {}", spaces);

}:!cargo run

warning: value assigned to `spaces` is never read

--> src/main.rs:3:13

|

3 | let mut spaces = spaces.len();

| ^^^^^^

|

= help: maybe it is overwritten before being read?

= note: `#[warn(unused_assignments)]` on by default

warning: `ch3_variables` (bin "ch3_variables") generated 1 warning

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.00s

Running `target/debug/ch3_variables`

The length of spaces is: 30I - don't know how to feel about this. On one hand I played around with the logic and found a way to turn an immutable into a mutable variable. On the other hand doing this inside a scope means that an inner scope spaces variable would be mutable and in the outer scope be immutable... I think this is exactly what the warning message during compilation is saying: "maybe it is overwritten before being read?".

Anyway, playing around with rust in this manner is cool, I'm pretty sure people have already figured out ways rust code can be manipulated terribly but my educated guess is that the compiler will try its best to stop anyone in situations like that.

Day 3

The second sub-chapter delves into Data Types.

From the book